In recent times small group meetings or home/cell groups are playing a seminal role in the church and in the life of believers. It happens in a time that there are huge “mega”-churches where thousands of people gather for worship service – even in one building and thus experience their religion on a massive scale. Impressive buildings, huge bands, organs, choirs and other mega-events enthrall people in such massive gatherings.

A small or home group, we understand now, can be an important way of experiencing spiritual growth next to these massive meetings. It is a group meeting which seeks to move away from loose, general talk. Of that we experience too much every moment of the day. This meeting, this discussion, is a spiritual discipline which seeks to focus on important spiritual material.

In spirituality traditions this type of discussions was regarded as a necessary and important spiritual discipline: communities gathered to speak about spiritual matters which they share on their spiritual journey with a clear spiritual aim and intention. They desire to experience a deepening of their faith, a clearer understanding and stronger commitment, but they also want to live this faith concretely and ask how their faith sends them out in this world and transforms them. Such discussions must bring the participants to live their faith.

Bit more is at stake than a growth in faith. In book 1.10.12 of his Imitation of Christ, Thomas a Kempis speaks about this discussion as spiritual discipline when he writes that such intimate gathering can be very important in the spiritual journey, especially where people who share a common faith in God are one in heart and mind.

It is the common faith in God which is seminal to remember here. For Thomas such a discussion about spiritual matters reflects an intimate connection between the participants and has nothing to do with informal, relaxed chatting. But even more so, the intimacy they share, is ultimately based on their being in the presence of God. In being together in such unity and focussing on spiritual matters, one is actually moving into the presence of God.

Though the small group meeting has tremendous social value and helps to overcome the alienation of people in our wide, harsh world, it is the religious value which really counts. Or, more precisely, its spiritual value is the significant factor.

The group meeting as spiritual discipline binds people together before God. It is the community with God which refreshes. It is a holy event which binds everyone in an intimate manner together before God.

This spiritual discipline need not be heavy and over-pious. It is not about our own self-righteous zeal to impress others and God.

It is a time and a meeting in which the faithful yearn to experience the words which give true life and which refreshes one to face new challenges on the spiritual journey. It is a time of concentration, a time in which to seek a recommitment, but most of all it is a time to be in the presence of God.

Friday, October 30, 2009

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Why Biblical Spirituality?

We return home tonight aftre three months of absence. This week I met colleagues in England to talk about Biblical Spirituality. We share a common interest and are now working together to discuss in more depth where we think we should go with our discipline.

During our meeting there was a spontaneous moment where we spoke about the fact that when one speaks about Biblical Spirituality one is deeply involved in the discipline from a perspective of faith. This was also my experience in the Netherlands where we agreed after a long discussion about many academic perspectives that Biblical Spirituality is a discipline which seeks from its participants faith, even holiness.

And, finally, it was a special moment to realize with my colleagues that we are involved in the discipline for no ulterior motives. It is because we think Biblical Spirituality is important, that the time is ripe for it and that it has an important role to play in Biblical Studies that we are involved in our discussions and activities.

It is enriching to share this common faith and commitment. Ultimately we reflect on Biblical Spirituality because it is what our faith asks from us.

During our meeting there was a spontaneous moment where we spoke about the fact that when one speaks about Biblical Spirituality one is deeply involved in the discipline from a perspective of faith. This was also my experience in the Netherlands where we agreed after a long discussion about many academic perspectives that Biblical Spirituality is a discipline which seeks from its participants faith, even holiness.

And, finally, it was a special moment to realize with my colleagues that we are involved in the discipline for no ulterior motives. It is because we think Biblical Spirituality is important, that the time is ripe for it and that it has an important role to play in Biblical Studies that we are involved in our discussions and activities.

It is enriching to share this common faith and commitment. Ultimately we reflect on Biblical Spirituality because it is what our faith asks from us.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

A prayer for my mum

In the Jewish museum in Berlin there is a tree on which visitors can hang a wish in the form of a card. When we visited early on a Sunday, there were already a number of cards in the tree. I read the messages, which are mostly beautifully written wishes that the holocaust would not be repeated in any form or that racism would have no place among us.

But there was one message written by a young boy. In it he writes a prayer that his mother may be healed from the terrible headaches from which she suffers so often.

And then we think the kids do not notice... or care....

But there was one message written by a young boy. In it he writes a prayer that his mother may be healed from the terrible headaches from which she suffers so often.

And then we think the kids do not notice... or care....

Sunday, October 25, 2009

Transformation - newness out of the ashes

In the Dallas Museum of Modern Art, designed by the brilliant Japannese architect, Toyo Ito and worth a visit already for the spirituality of this breathtakingly beautiful design, hangs this painting by Anselm Kiefer with the title Ash-Flower (painted 1983-1997).

A part of the museum:

Kiefer, a German born in 1948, came to terms with his German identity with this painting as well. The painting portrays the grand room of the Reichskansellei In Berlin. The room is empty. Kiefer covered the painting with ash. The only object is a tall dried sunflower plant. With this painting he depicts transformation: from the ashes, the destruction, grows a new image.

Transition is a key element in spirituality. Spirituality focuses on relationships, which can, obviously, be destructive. But at the same time where relationships are dynamic, transformative, new things can happen. Hope remains. There is still light. In Christian spirituality this transformation is decisive.

This painting is so beautiful. It was my second visit and each time I am impressed by it more and more. We see through a mirror, through darkness ashes. Our flowers are dry, but they speak of the sun which gives light where dark ashes are all that we thought remained.

A part of the museum:

Kiefer, a German born in 1948, came to terms with his German identity with this painting as well. The painting portrays the grand room of the Reichskansellei In Berlin. The room is empty. Kiefer covered the painting with ash. The only object is a tall dried sunflower plant. With this painting he depicts transformation: from the ashes, the destruction, grows a new image.

Transition is a key element in spirituality. Spirituality focuses on relationships, which can, obviously, be destructive. But at the same time where relationships are dynamic, transformative, new things can happen. Hope remains. There is still light. In Christian spirituality this transformation is decisive.

This painting is so beautiful. It was my second visit and each time I am impressed by it more and more. We see through a mirror, through darkness ashes. Our flowers are dry, but they speak of the sun which gives light where dark ashes are all that we thought remained.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

I have been wanting to visit this church for a long time now. And on our way home from Berlin I could finally experience the fulfillment of this dream. We stop at Dresden. It is a city which was destroyed extensively in the second World War. The Friedenskirche (Peace Church), previously in East Germany and a beacon of Dresden in pre-war Germany, was almost completely destroyed, but then restored after 13 years of rebuilding at a cost of 180, 000, 000 Euro's. Many people and institutions helped with donations - amongst others a Nobel Price Winner who donated his prize. It was finally rededicated in 2005.

The building which survived many wars, finally collapsed after 650,000 fire bombs were thrown on the city and the heat made the structure implode.

The communists wanted to convert it in a parking garage, but the locals resisted. The church played a huge role in the peace movement in East Germany which finally lead to the collapse of the Communist state.

It is today one of the best known churches in Germany. Pres. Obama visited earlier this year. Many tourist, actually droves of them, visit. The church has become a symbol in more ways than one and speaks of new life which can be born from war and destruction.

We begin our visit with high expectations. Dresden is not Berlin, and yet, one sees signs of new life and hope in many unexpected place - like the panel above a door of a shop near the church:

A big statue of Luther stands next to the church. It is a young, powerful Luther:

It is disturbing to see how the church was destroyed. Here is a picture:

Here is the restored church:

This is the liturgical space (with many tourists)...

Another part of the liturgical space:

The church is painted with pastel colours. It creates a feeling of space, lightness:

Having visited many cathedrals during our stay, it struck me suddenly that the pulpit is in the centre of the church, which indicated its protestant character:

Another part of the liturgical space:

In the big cellar of the church there is an exhibition of memorial stones which were discovered amongs the ruins. There are beautiful comments in the room about their witness to saints of previous generations, but also to the continuing hope on the resurrection.

This picture of praying woman struck me. I went back to take a picture of the praying hands. It has a mystical effect.

There is in the cellar with its chapel also an altar stone by the British sculpture, Arish Kapoor. The hole in the middle symbolizes the deeper dimension of our life which is lost in our superficial existence.

On our way back, sadly, we walked pass this person with his red flag. He has not found freedom....

This was a special visit which affected me more than I expected. I realised once again how destructive war can be. In this case it took away from the community in Dresden a precious symbol. To see how thousands of them over many years worked to get it rebuilt, is both touching and sad.

It was a special visit.

The building which survived many wars, finally collapsed after 650,000 fire bombs were thrown on the city and the heat made the structure implode.

The communists wanted to convert it in a parking garage, but the locals resisted. The church played a huge role in the peace movement in East Germany which finally lead to the collapse of the Communist state.

It is today one of the best known churches in Germany. Pres. Obama visited earlier this year. Many tourist, actually droves of them, visit. The church has become a symbol in more ways than one and speaks of new life which can be born from war and destruction.

We begin our visit with high expectations. Dresden is not Berlin, and yet, one sees signs of new life and hope in many unexpected place - like the panel above a door of a shop near the church:

A big statue of Luther stands next to the church. It is a young, powerful Luther:

It is disturbing to see how the church was destroyed. Here is a picture:

Here is the restored church:

This is the liturgical space (with many tourists)...

Another part of the liturgical space:

The church is painted with pastel colours. It creates a feeling of space, lightness:

Having visited many cathedrals during our stay, it struck me suddenly that the pulpit is in the centre of the church, which indicated its protestant character:

Another part of the liturgical space:

In the big cellar of the church there is an exhibition of memorial stones which were discovered amongs the ruins. There are beautiful comments in the room about their witness to saints of previous generations, but also to the continuing hope on the resurrection.

This picture of praying woman struck me. I went back to take a picture of the praying hands. It has a mystical effect.

There is in the cellar with its chapel also an altar stone by the British sculpture, Arish Kapoor. The hole in the middle symbolizes the deeper dimension of our life which is lost in our superficial existence.

On our way back, sadly, we walked pass this person with his red flag. He has not found freedom....

This was a special visit which affected me more than I expected. I realised once again how destructive war can be. In this case it took away from the community in Dresden a precious symbol. To see how thousands of them over many years worked to get it rebuilt, is both touching and sad.

It was a special visit.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Revealing a wounded world. A visit to Berlin.

On the way home from the conference in Nijmegen (previous blog), we travelled via Berlin. I last visited there before the unification of the two Germanies and wanted to visit again for some time now.

And what a transformation. It is now a beautiful city. The old East Berlin, previously grey and dark and menacing, where I once visited with trepidation, is now full of life, with some beatiful new buildings. It is actually ironical that the old part now looks newer than the previously Western parts of Berlin.

But there are deep wounds in Berlin.

I woke up this morning with a radio program on a new Institute for the study of Nazism which has been established in Bavaria. They interviewed someone who recalls the times of Hitler: "The people went crazy," she says. "In our town, some of the people literally went weeks without washing their hands after they met Hitler and shook hands with him. They worshipped the man. Crazy,” she says. “Everyone” was crazy.

It was a time of mass hysteria.

In the Jewish museum last Sunday in Berlin I experienced the offshoots and results of such mass movements again. What an extraordinary museum by Liebeskind. The exhibitions, excellently prepared and informative about Jewish religion, culture and history are not sensational. They are good to see. But the symbolism of the building is staggering, as some of my pictures show(see below).

In the museum, there is disturbing documentation of the suffering of people because of the simple fact that they were Jewish. The holocaust items almost break my heart. It is about violence unleashed in all its anger (cf. Photo’s below).

Will there, I thought, at some moment, ever be something as cruel as this again? And, suddenly I remember the wall – again in Germany and the thousands of people who tried to reach freedom and were killed simply because they wanted to leave their own country. And I remember apartheid, Mashonaland where security people killed more than 20000 Ndebeles in 1985, Srebrenica where more than 8000 men were killed by the Serbs in 1995, and the mass killings in Rwanda. Even if nothing equals the shoa, evil still remains among us, in us and regularly explodes in new forms of murder.

Yes, there will be violence. People have it in them for this to happen time and again. It is not only in Germany where this happens. It happens in our world.

Our hotel where we stay in Berlin is modern. Only later we are told that it was built on the site where the wall once stood. Berlin retained the traces of the wall by building a double brick track in the streets where it once stood (cf. Picture). And, on closer inspections, we see the track and how it surrounds our hotel. What a symbol of the value of freedom, and, also, of how precious humanity is. The symbolism of that track remains with me ever since.

Berlin carries the wounds of the world on its body.

The place where the Berlin wall stood, is marked by a parth of two bricks in the road (on the right hand side, where the cars are parked): what a symbol!Our hotel stood on the location where the wall was.

Note its path around the corner of the opposite sidewalk:

In the museum Liebeskind designed hauntingly beautiful empty rooms to symbolize the absence of Jews from German society:

In another empty room there is a sculpture called "Fallen leaves" by Radeshna. The leaves are faces, made from metal. They cover the floor (10 000) and symbolize the victims of war and violence. I was told by a security guard that visitors are allowed to walk on them. The clanging noise of metal against metal remains with me.

These images from a concentration camp haunt our collective memory:

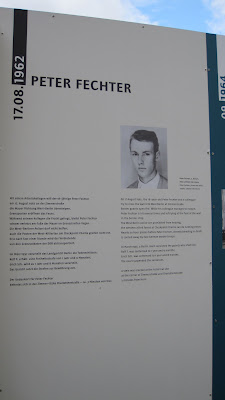

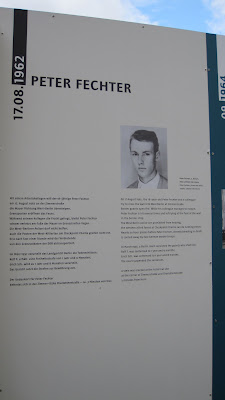

He was 18 years old in 1962 when he fled his own country to freedom together with his friend. He was shot. Twenty years later the soldier who shot him was sentenced to a year's imprisonment. His name was Peter Fechter. Eighteen years old, yearning for freedom:

And what a transformation. It is now a beautiful city. The old East Berlin, previously grey and dark and menacing, where I once visited with trepidation, is now full of life, with some beatiful new buildings. It is actually ironical that the old part now looks newer than the previously Western parts of Berlin.

But there are deep wounds in Berlin.

I woke up this morning with a radio program on a new Institute for the study of Nazism which has been established in Bavaria. They interviewed someone who recalls the times of Hitler: "The people went crazy," she says. "In our town, some of the people literally went weeks without washing their hands after they met Hitler and shook hands with him. They worshipped the man. Crazy,” she says. “Everyone” was crazy.

It was a time of mass hysteria.

In the Jewish museum last Sunday in Berlin I experienced the offshoots and results of such mass movements again. What an extraordinary museum by Liebeskind. The exhibitions, excellently prepared and informative about Jewish religion, culture and history are not sensational. They are good to see. But the symbolism of the building is staggering, as some of my pictures show(see below).

In the museum, there is disturbing documentation of the suffering of people because of the simple fact that they were Jewish. The holocaust items almost break my heart. It is about violence unleashed in all its anger (cf. Photo’s below).

Will there, I thought, at some moment, ever be something as cruel as this again? And, suddenly I remember the wall – again in Germany and the thousands of people who tried to reach freedom and were killed simply because they wanted to leave their own country. And I remember apartheid, Mashonaland where security people killed more than 20000 Ndebeles in 1985, Srebrenica where more than 8000 men were killed by the Serbs in 1995, and the mass killings in Rwanda. Even if nothing equals the shoa, evil still remains among us, in us and regularly explodes in new forms of murder.

Yes, there will be violence. People have it in them for this to happen time and again. It is not only in Germany where this happens. It happens in our world.

Our hotel where we stay in Berlin is modern. Only later we are told that it was built on the site where the wall once stood. Berlin retained the traces of the wall by building a double brick track in the streets where it once stood (cf. Picture). And, on closer inspections, we see the track and how it surrounds our hotel. What a symbol of the value of freedom, and, also, of how precious humanity is. The symbolism of that track remains with me ever since.

Berlin carries the wounds of the world on its body.

The place where the Berlin wall stood, is marked by a parth of two bricks in the road (on the right hand side, where the cars are parked): what a symbol!Our hotel stood on the location where the wall was.

Note its path around the corner of the opposite sidewalk:

In the museum Liebeskind designed hauntingly beautiful empty rooms to symbolize the absence of Jews from German society:

In another empty room there is a sculpture called "Fallen leaves" by Radeshna. The leaves are faces, made from metal. They cover the floor (10 000) and symbolize the victims of war and violence. I was told by a security guard that visitors are allowed to walk on them. The clanging noise of metal against metal remains with me.

These images from a concentration camp haunt our collective memory:

He was 18 years old in 1962 when he fled his own country to freedom together with his friend. He was shot. Twenty years later the soldier who shot him was sentenced to a year's imprisonment. His name was Peter Fechter. Eighteen years old, yearning for freedom:

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Sober mysticism. On the mysticism of Thomas A Kempis.

On a wintry day in Regensburg (icycles on the hedge)

I saw three aircraft flying in tandem and took a photo

But the birds intervened and said: why do you forget us?

During my visit to Nijmegen last Friday I participated with Huub Welzen, one of the veterans in the field of Biblical Spirituality, in a small conference on Biblical Spirituality. It was a special experience to discuss the field with colleagues who have been involved in it for some time now.

During our discussions it struck me how relatively undeveloped the discipline is, even though it is clearly an important new field of study.

I shared my experiences with our Master’s course in Biblical Spirituality at my university with the group in Nijmegen. For this, I had to evaluate the course which was presented over the last two years and which is presently being brought to conclusion. It was a special experience for me to think about this course and to share my reflection. I realized even more than before how much the two year course meant to me personally and academically. It was indeed a time of growth. We were privileged to have had a group of gifted students whose participation in the course provided a valuable input.

I learnt a lot from sharing my evaluation with the group in Nijmegen: their comments and the discussion helped me to gain more clarity and gave me some new ideas to reflect on.

But my visit brought me another, unexpected surprise. Jos Huls and Hein Blommestijn gave me the 2006 book, “Nuchtere Mystiek” (Sober / Realistic Mysticism) with contributions by Kees Waaijman and his colleagues. The book is a result of the 25th study week of the Titus Brandsma Institute. I have begun reading it and was pleasantly surprised and excited by its contents. It is an informative publication at the hand of which I wish to reflect a bit more about mysticism and Thomas – something which kept me quite busy the last couple of months.

Recently, during my reading of Thomas a Kempis’ Imitiation of Christ I often wondered whether one could regard him as a mystic. He writes practically and concretely about discipleship, about the imitation fo Christ. One could without doubt regard him as a spirituality author, writing about the relationship of God and humanity which is transformative for the whole of one’s life. But is he really a mystic, someone who reflects about the unio mystica? Is he reallty amidst all the wisdom someone who writes about the union with God?

Previously I did not think so. I was misled by the overwhelmingly concrete character and practical wisdom which is prominent in the book.

But according to this book of Waaijman and others, Thomas is a mystic in a consistent manner. In each of the four parts of his Imitation he reveals that the life of discipleship is about something much deeper. He is profoundly interested in the mystical union with God. Here is one argument they offer:

It is true that the first of the four books focus on how the believer imitates Christ through an active seeking of transformation and devotion. But, comments Rudolf van Dijk (who translated the Imitation in contemporary Dutch) on page 47, this active input is given its deepest meaning when it happens, according to Thomas, in response to God’s word. Thomas expresses this clearly very early in his first book (1.3.10-12).

I am immediately interested in this observation. So I consult Van Dijk’s translation of this passage. (Conveniently the Latin text is also given next to the translation).

It is, interestingly, a prayer, inserted quite unexpectedly in the midst of Thomas' reflection of the imitation.

With this prayer, the discussion in the first book is given a deeper dimension. The heading of the chapter is “On teaching the Truth” - quite impressive. But it is a prayer which celebrates the powerful transformation which take place when God speaks. Behind all our activities, spelled out in this section, I now understand Thomas to say, stands God’s life-giving touch.

Immediately a whole world opens before me and my question about Thomas’ mysticism is addressed: Here, at the very beginning of his book, Thomas suddenly switches from his meditative approach, his discussion of the imitation of Christ, to an orative stance (a moment in the hermeneutical process which is much neglected). Whilst he is still writing on "teaching the truth," out of the blue he begins to pray . Meditatio is followed, or, interrupted by oratio.

And, remembering that I have been writing on silence in the previous blogs, I am also struck by the role silence plays in this prayer: The prayer is as follows: “O truth, God, make me one with You in love which continues eternally.” The Latin “fac me unum” is clear: Make me one with You. This is all about the mystical yearning for God and the desire to be unified with God. And what is more, when one speaks about “truth,” it is not about knowledge or facts or wisdom. Thomas personifies truth: to speak about truth, is to talk about God; to teach truth is to be with God.

Here, in the midst of all the practical wisdom of Thomas, he is moved to pray – almost as if his thoughts are no longer under control. He addresses God directly. Truth is about wanting to be with God, but the desire for truth inevitably brings one to want to pray and speak directly with God. And the first thing he then expresses in prayer is the desire to be one with God. No-thing (!) like “make me a good disciple / follower of Christ.” Just: make me one with You.

Thomas is in effect saying: “Everything I do and live, is directed towards union with God.” But it is even more gripping to note what the end result of this unity is: Make me one with you in eternal love, love which continues without end (in caritate perpetua – beautiful the “caritate”). When one yearns for God, it is a desire to be with God in love (reminds me of Hadewych of Antwerp and her spirituality of love).

Then Thomas continues, with a little bit of humour: “Reading and listening to many things makes me weary.” He is busy with teaching the truth here and teaching has many wise people talking. This confession of weariness reveals another mystical dimension of the mystical experience: to the mystic all our human activities, our speaking and our talking, are nothing-ness. They need to disappear because they can stand in the way of our relationship with God. Reading (words!), listening (words!) are nothing but burdensome.

Then follows his deepest knowledge, spoken in the following part of the prayer: “In You is everything I will and desire” (volo et desidero). To be with God and God is what really matters, is the deepest desire of his heart.

This is so important that Thomas repeats it. He does this by explicitly mentioning silence: “let all the wise teachers be silent. Let all creatures say nothing before Your countenance. You alone must speak to me.” Silence is the right attitude before God. We do not speak about all our activities, our piety, our imitation of Christ. We are focussed away from ourselves.

It is God’s Word which creates discipleship, which brings one to love. It is when we fall silent, when we say nothing more, that we shall be able to hear God’s words of life. Our own chattering and talking are useless and burdensome.

Only in God’s presence we shall find the words of life (Samaria, the woman, the fountain!) – and we also know, when God speaks, universes are created (Genesis – the beginning).

One easily reads over the prayer. And yet, it gives a completely different perspective on the Imitation.

Interpreters often say the most important parts of a text, those parts which give meaning to a text, are the parts that are unique.

I saw three aircraft flying in tandem and took a photo

But the birds intervened and said: why do you forget us?

During my visit to Nijmegen last Friday I participated with Huub Welzen, one of the veterans in the field of Biblical Spirituality, in a small conference on Biblical Spirituality. It was a special experience to discuss the field with colleagues who have been involved in it for some time now.

During our discussions it struck me how relatively undeveloped the discipline is, even though it is clearly an important new field of study.

I shared my experiences with our Master’s course in Biblical Spirituality at my university with the group in Nijmegen. For this, I had to evaluate the course which was presented over the last two years and which is presently being brought to conclusion. It was a special experience for me to think about this course and to share my reflection. I realized even more than before how much the two year course meant to me personally and academically. It was indeed a time of growth. We were privileged to have had a group of gifted students whose participation in the course provided a valuable input.

I learnt a lot from sharing my evaluation with the group in Nijmegen: their comments and the discussion helped me to gain more clarity and gave me some new ideas to reflect on.

But my visit brought me another, unexpected surprise. Jos Huls and Hein Blommestijn gave me the 2006 book, “Nuchtere Mystiek” (Sober / Realistic Mysticism) with contributions by Kees Waaijman and his colleagues. The book is a result of the 25th study week of the Titus Brandsma Institute. I have begun reading it and was pleasantly surprised and excited by its contents. It is an informative publication at the hand of which I wish to reflect a bit more about mysticism and Thomas – something which kept me quite busy the last couple of months.

Recently, during my reading of Thomas a Kempis’ Imitiation of Christ I often wondered whether one could regard him as a mystic. He writes practically and concretely about discipleship, about the imitation fo Christ. One could without doubt regard him as a spirituality author, writing about the relationship of God and humanity which is transformative for the whole of one’s life. But is he really a mystic, someone who reflects about the unio mystica? Is he reallty amidst all the wisdom someone who writes about the union with God?

Previously I did not think so. I was misled by the overwhelmingly concrete character and practical wisdom which is prominent in the book.

But according to this book of Waaijman and others, Thomas is a mystic in a consistent manner. In each of the four parts of his Imitation he reveals that the life of discipleship is about something much deeper. He is profoundly interested in the mystical union with God. Here is one argument they offer:

It is true that the first of the four books focus on how the believer imitates Christ through an active seeking of transformation and devotion. But, comments Rudolf van Dijk (who translated the Imitation in contemporary Dutch) on page 47, this active input is given its deepest meaning when it happens, according to Thomas, in response to God’s word. Thomas expresses this clearly very early in his first book (1.3.10-12).

I am immediately interested in this observation. So I consult Van Dijk’s translation of this passage. (Conveniently the Latin text is also given next to the translation).

It is, interestingly, a prayer, inserted quite unexpectedly in the midst of Thomas' reflection of the imitation.

With this prayer, the discussion in the first book is given a deeper dimension. The heading of the chapter is “On teaching the Truth” - quite impressive. But it is a prayer which celebrates the powerful transformation which take place when God speaks. Behind all our activities, spelled out in this section, I now understand Thomas to say, stands God’s life-giving touch.

Immediately a whole world opens before me and my question about Thomas’ mysticism is addressed: Here, at the very beginning of his book, Thomas suddenly switches from his meditative approach, his discussion of the imitation of Christ, to an orative stance (a moment in the hermeneutical process which is much neglected). Whilst he is still writing on "teaching the truth," out of the blue he begins to pray . Meditatio is followed, or, interrupted by oratio.

And, remembering that I have been writing on silence in the previous blogs, I am also struck by the role silence plays in this prayer: The prayer is as follows: “O truth, God, make me one with You in love which continues eternally.” The Latin “fac me unum” is clear: Make me one with You. This is all about the mystical yearning for God and the desire to be unified with God. And what is more, when one speaks about “truth,” it is not about knowledge or facts or wisdom. Thomas personifies truth: to speak about truth, is to talk about God; to teach truth is to be with God.

Here, in the midst of all the practical wisdom of Thomas, he is moved to pray – almost as if his thoughts are no longer under control. He addresses God directly. Truth is about wanting to be with God, but the desire for truth inevitably brings one to want to pray and speak directly with God. And the first thing he then expresses in prayer is the desire to be one with God. No-thing (!) like “make me a good disciple / follower of Christ.” Just: make me one with You.

Thomas is in effect saying: “Everything I do and live, is directed towards union with God.” But it is even more gripping to note what the end result of this unity is: Make me one with you in eternal love, love which continues without end (in caritate perpetua – beautiful the “caritate”). When one yearns for God, it is a desire to be with God in love (reminds me of Hadewych of Antwerp and her spirituality of love).

Then Thomas continues, with a little bit of humour: “Reading and listening to many things makes me weary.” He is busy with teaching the truth here and teaching has many wise people talking. This confession of weariness reveals another mystical dimension of the mystical experience: to the mystic all our human activities, our speaking and our talking, are nothing-ness. They need to disappear because they can stand in the way of our relationship with God. Reading (words!), listening (words!) are nothing but burdensome.

Then follows his deepest knowledge, spoken in the following part of the prayer: “In You is everything I will and desire” (volo et desidero). To be with God and God is what really matters, is the deepest desire of his heart.

This is so important that Thomas repeats it. He does this by explicitly mentioning silence: “let all the wise teachers be silent. Let all creatures say nothing before Your countenance. You alone must speak to me.” Silence is the right attitude before God. We do not speak about all our activities, our piety, our imitation of Christ. We are focussed away from ourselves.

It is God’s Word which creates discipleship, which brings one to love. It is when we fall silent, when we say nothing more, that we shall be able to hear God’s words of life. Our own chattering and talking are useless and burdensome.

Only in God’s presence we shall find the words of life (Samaria, the woman, the fountain!) – and we also know, when God speaks, universes are created (Genesis – the beginning).

One easily reads over the prayer. And yet, it gives a completely different perspective on the Imitation.

Interpreters often say the most important parts of a text, those parts which give meaning to a text, are the parts that are unique.

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Silence can speak louder than words: On Psalm 62

We sometimes talk about “silent” prayer, referring through this expression to prayers which we say by ourselves, in our thoughts.

It would seem strange and even embarrassing, we think, if someone would ask us to pray silence. Prayer, we assume is about “words,” it has to do with “talking."

Compare with this the well-known Psalm 65 which which is mostly translated as, “Praise is due to you, O God.” This translation reveals the prejudice against silence, especially in prayers. Literally the verse reads: "There will be silence before You, O God.” Or: “You are praised with silence in Zion, O God.” (GWT).

Here the Psalmist speaks about silent prayer in the sense of praying silence, or, worshipping God with silence.

Compare with this also Psalm 62 on the silent waiting on God:

My soul waiteth in silence for God only: 2 He only is my rock and my salvation: 3 How long will ye set upon a man, 4 They only consult to thrust him down from his dignity; 5 My soul, wait thou in silence for God only; 6 He only is my rock and my salvation: 7 With God is my salvation and my glory.

Compare this with Psalm 131 (cf my previous blogs) where the Psalmist calmed and quieted his soul, "like a weaned child with its mother." In both these Psalms silence is the desire of the Psalmist. And, indeed, how necessary is it to calm one’s soul in the light of our busy thoughts and feelings so that one can focus on speaking to God.

When we pray, we often struggle to find inner peace and to focus on our prayers. As we pray we think about many other things than our relationship with God and our prayer. Our problems, anxieties, thoughts of the day keep us busy even in times of reflection and meditation. These are the things, the "vanities" which the Psalmist wishes to leave behind in Psalm 131. He brings himself to silence, to the quiet understanding that it is good to be with God.

It implies also that one does not have to speak when in the divine presence. One can be like the little baby who is at peace with the one who fed her or him. One becomes quiet and realises one can remain quiet, silent and in peace in the divine presence.

But here we should think deeper: when my soul is quiet and at peace, when I feel no need to speak, when the vanities have been abandoned, silence has come to me in a deeper manner. Then one is still unto God (not before God). Then we realize that we are in the presence of God who transcends all understanding and all words. It is a moment when we can discover that our words, human words do not help us to reach God. We receive the grace to rest in God's grace, beyond our human attempts to grasp God.

It is also the time to reflect on the deepest of mysteries: Not only is God in any case ineffable, beyond human words, but long before we have spoken, God has reached out to us, yearning to relate to us in love.

Why should I be caught up in my language, my words when God knows, long before I have spoken, the deepest desires and thoughts of my heart? My silence can speak a thousand words, can speak the deepest of mysteries. It can talk loudly of my complete, wordless trust in the mercy of the God of all things.

It is not what we say in prayer which establishes a relationship with God. God has embraced me as loving Father, long before I could recite my little speeches which I have prepared so carefully on my way home. God is there, my rock, my salvation, the power in my life.

Not my words, but my openness for God’s reaching out to me, is what really matters. The prayer of silence unto God, without words, talking, chatting, loaded with the silence of trust and peace, reflects the conviction that no language or words can explain God or can even establish being with God. It may just be that our silence of yearning and desire to be with God will make us deeper aware of the mystical nearness of God.

There is a parallel: often, in times we share with our families, we speak much. When we meet after times of absence, there is much to talk about, to share. We tell many stories and share many thoughts. But then, after a while, we fall silent. We even feel the need not to talk much, but just be with each other. Then we enjoy each other’s presence. There are not many words, but there are feelings of joy, warmth and appreciation. These are times of peace. These quiet times are filled. They overflow with love. And what is true in our everyday lives, is also true of our relationship with God. Love speaks in words, but can do so even more in silence.

It would seem strange and even embarrassing, we think, if someone would ask us to pray silence. Prayer, we assume is about “words,” it has to do with “talking."

Compare with this the well-known Psalm 65 which which is mostly translated as, “Praise is due to you, O God.” This translation reveals the prejudice against silence, especially in prayers. Literally the verse reads: "There will be silence before You, O God.” Or: “You are praised with silence in Zion, O God.” (GWT).

Here the Psalmist speaks about silent prayer in the sense of praying silence, or, worshipping God with silence.

Compare with this also Psalm 62 on the silent waiting on God:

My soul waiteth in silence for God only: 2 He only is my rock and my salvation: 3 How long will ye set upon a man, 4 They only consult to thrust him down from his dignity; 5 My soul, wait thou in silence for God only; 6 He only is my rock and my salvation: 7 With God is my salvation and my glory.

Compare this with Psalm 131 (cf my previous blogs) where the Psalmist calmed and quieted his soul, "like a weaned child with its mother." In both these Psalms silence is the desire of the Psalmist. And, indeed, how necessary is it to calm one’s soul in the light of our busy thoughts and feelings so that one can focus on speaking to God.

When we pray, we often struggle to find inner peace and to focus on our prayers. As we pray we think about many other things than our relationship with God and our prayer. Our problems, anxieties, thoughts of the day keep us busy even in times of reflection and meditation. These are the things, the "vanities" which the Psalmist wishes to leave behind in Psalm 131. He brings himself to silence, to the quiet understanding that it is good to be with God.

It implies also that one does not have to speak when in the divine presence. One can be like the little baby who is at peace with the one who fed her or him. One becomes quiet and realises one can remain quiet, silent and in peace in the divine presence.

But here we should think deeper: when my soul is quiet and at peace, when I feel no need to speak, when the vanities have been abandoned, silence has come to me in a deeper manner. Then one is still unto God (not before God). Then we realize that we are in the presence of God who transcends all understanding and all words. It is a moment when we can discover that our words, human words do not help us to reach God. We receive the grace to rest in God's grace, beyond our human attempts to grasp God.

It is also the time to reflect on the deepest of mysteries: Not only is God in any case ineffable, beyond human words, but long before we have spoken, God has reached out to us, yearning to relate to us in love.

Why should I be caught up in my language, my words when God knows, long before I have spoken, the deepest desires and thoughts of my heart? My silence can speak a thousand words, can speak the deepest of mysteries. It can talk loudly of my complete, wordless trust in the mercy of the God of all things.

It is not what we say in prayer which establishes a relationship with God. God has embraced me as loving Father, long before I could recite my little speeches which I have prepared so carefully on my way home. God is there, my rock, my salvation, the power in my life.

Not my words, but my openness for God’s reaching out to me, is what really matters. The prayer of silence unto God, without words, talking, chatting, loaded with the silence of trust and peace, reflects the conviction that no language or words can explain God or can even establish being with God. It may just be that our silence of yearning and desire to be with God will make us deeper aware of the mystical nearness of God.

There is a parallel: often, in times we share with our families, we speak much. When we meet after times of absence, there is much to talk about, to share. We tell many stories and share many thoughts. But then, after a while, we fall silent. We even feel the need not to talk much, but just be with each other. Then we enjoy each other’s presence. There are not many words, but there are feelings of joy, warmth and appreciation. These are times of peace. These quiet times are filled. They overflow with love. And what is true in our everyday lives, is also true of our relationship with God. Love speaks in words, but can do so even more in silence.

Labels:

ineffable.,

Love Silence Relationship

Monday, October 19, 2009

To pray silence

(Beautiful photo with silence as theme - taken by Gaute Bruvik)

Prayer, we sometimes say is not about our needs as it is about praising God. And adoration of God is indeed an important part of the spiritual journey. To worship God in awe and gratitude can be a mystical experience in itself. When God touches us, praise comes up spontaneously from our innermost being. We marvel that we are given the grace of a divine touch. Words stream from us to express our joy at the mystical, special moment of the divine touch.

As we sing out the joy of having met God, it brings us even closer to God. We express our mystical experience and in our expression we deepen that experience. To worship God, is to enrich our mystical experience. We utter our words and speak out our feelings, but ultimately God takes our words, our expressions, our feelings and our experiences and uses it, sanctifies it. We worship and praise God because we were touched by God. But then, in abundant grace, God touches us in and through our worship. As we express from our side, our response to the mystical touch of God, we are touched anew.

All this makes our prayers of worship special. We do not speak about ourselves and our needs. We adore God and focus on the divine praise. And we get to understand that even if we are praising God, our words are sanctified, or experiences deepened. We worship God because of the divine touch, but then – in abundant grace, we realise with awe that in our worship God is touching us again.

It is enough to make us quiet. Often we arrive at a point that we understand how special our relationship with God is, how extraordinary our worship of the divine. It transcends our words. We cannot find language to express our experience. We fall silent, we run out of words. We merely want to be with God.

Which makes me think of Psalm 131.

1My heart is not proud, O Lord, my eyes are not haughty; I do not concern myself with great matters or things too wonderful for me. 2 But I have stilled and quieted my soul; like a weaned child with its mother, like a weaned child is my soul within me. 3 O Israel, put your hope in the Lord both now and forevermore” (NIV).

What a remarkable Psalm: it is short, scarcely 30 words long. It is as if the author wants to speak the minimum of words. He has not much to say. Praying to God, the author speaks of his simplicity and humility. The simplicity is then linked with his quietness, his silence. This silence is so special that he uses an image to express it: he is like a baby, happy, contented, quiet and silent. It is a prayer about not praying words, not saying big, vain things.

And then the overwhelming end of the Psalm: to hope on God is literally to “wait on God.” Many translations render this verse as “hoping.” But in the light of the preceding verses, it should be seen as “waiting,” In this Psalm the author says: My words have come to an end. I only want to pray about having fallen silent. I want to pray about abandoning all the noise in life, of letting go the “important” things. I am praying silently in silence.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

To wait silently on God.

We often talk a lot when we pray. Our hearts desire so many things that we cannot stop speaking. We fill ou prayers with words. We have much to ask God, much to say to God.

And this is good. God desires that we pray.

But there is a negative side to such talking. To talk to God, has its place and time. But we need to listen to God in the first place and we need to hear what God says to us. A word of God can refresh us, restore us, transform us, inspire us and bring new life to us. It can bring our desires to fulfillment. It can full us with peace – something our own words and thoughts can never do.

This is why we read the Bible and listen to the witnesses of saints of all times. If we talk too much, we will hear only the echo of our own words. We become captives of our own talkativeness, of our own thoughts and words. We are so caught up by what we want to say and what we speak, that we are not receptive for words of God.

That is why it is a good exercise to read the Bible – and, importantly, to begin this in silence. We “wait” on the Lord. It is a “quiet” time in which we are preparing, making ourselves ready for what God has to say to us.

This is even more important in the light of the fact that the Bible speaks “softly” about God. The authors of Biblical books want to speak about God in broken, restricted human language, whilst God is much greater than language and cannot be contained in our human speech. How can we ever express who God in in language? God is ineffable. When we speak about God, we can only do so haltingly, humbly, knowing we are trying to do the impossible. Who can ever express the divine mystery in human words?

It was the great challenge for Biblical authors to communicate their experiences of God. When we listen to them, we wait in silence to hear what they are saying, so that we can understand well, experience something of what they were experiencing. We must be careful not to let our words interfere and block what they were trying to say. And we need to be careful to experience what they were expressing in their witness. So we are asked in more than one way to wait in silence to hear them clearly, to let their soft words of God penetrate our minds and hearts.

So we take up their books in silence, even in awe. Silence prepares our hearts for what they are about to witness to us. We open the books in silence, we listen to them in silence and we allow the words to echo in our hearts and to penetrate our minds – long before we even think of responding to them. In 1 Kings 19 Elijah heard a thunder storm , an earthquake and fire. But God was not in this noise. Then came the silence. And God was in the silence.

I want to think and write more about this in the next few days.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

How does one read the Bible? On holiness as requirement for understanding the Bible!

The question is often asked "how do we read the Bible"? And answers are found by investigating its contents. But before we can even consider reflecting on the meaning of the Biblical message, we need to ask with what attitude do we read the Bible.

Biblical Studies began during the Enlightenment as a real discipline in which readers began to “study” the Bible in a “scientific”, learned manner. In this period they stressed that the Bible was a human book with a human face. Biblical Studies slowly became a science in which the Bible was considered to be a book like any other book. We can only understand it fully, it was said, if we acknowledge its human, restricted nature.

For many readers of the Bible, this was a liberating approach. For them it was nothing else than confessing about the Bible what they were saying about the Incarnation: the Word became flesh and lived among us. We touched it, saw it, heard it – the Word was truly human. This focus on the human nature of the Bible explained many problems which readers had with the Bible, without necessarily contradicting that the Bible was a book of faith. It was, after all, a book in which humanity confesses in human language its searching, exploring and often frail faith in God .

For some it even enhanced the special nature of the Bible: Exactly because of the many voices in the Bible of people who sincerely struggled to express their deep belief in a God who reaches out to humanity, the Bible stirred hearts and transformed people. People identified with such an approach.

And yet, as Biblical Studies developed, especially in recent times with the literary and narratological readings of the Bible, the Bible was regarded as a “text.” Biblical books were seen as written documents with a certain narrative, rhetorical and literary structure and function. So the process which took place since the Enlightenment continued, increased and is now at a place where the text became less “human” and more “object.”

So today we speak almost consistently of the Bible as “book”, as “text”, as “narrative.” We lay it on an operation table and dissect it to our own satisfaction and with great curiosity.

This is obviously a good thing – we pay minute attention to the text and take great care to understand it well. But in the meantime, the Bible wishes to be much more than that. One the one hand, it wants to be a divine voice, representing God’s words. On the other hand, it wants to be the words of John, Matthew, Mark, Paul and James. They speak, indeed in a human form, about how God touched and transformed humanity. We do not have a text, schluss, but we have voice in word who speak and communicate with us over the centuries.

To hold on to the fact that people wrote this Bible and speak to us, is highly significant. The reader of the Bible has to keep this constantly in mind. It is common courtesy to hear the other person out, to allow the other one to speak to me – and not to make them the object of my speech only.

It is even more so when that one shares his or her intimate, special thoughts with us. We listen to them because we hear words from their heart. It is a deeply respectful attitude which is required from us. One is even more respectful when someone shares his or her innermost feelings about his or her ultimate values. So one listens with respect. We see that person like others do not. We even see him or her as we do not often perceive them.

It is not so easy to listen to others. By listening to the other person, I put myself at risk. It may just be that I may be touched by his or her words. The words may stay with me, haunt me, inspire me or make me feel despair. They may even change my life forever. Their words may make me do things which I normally would not do. I do take on a special responsibility by entering into a conversation with the other.

This is even more the case with Biblical texts. They speak about a God who is holy whom Biblical authors experienced in all the divine power. Take off your shoes, Moses is told, before the consuming fire. You must be aware that you are in the presence of the Holy. You need to be holy yourself, without shoes, without anything which may be impure in the divine Presence.

The Bible is a text, yes. But it is also, we are told text-wise, something deeper and more than a text. It is a book full of words of people who have been inspired by the divine, ultimate being. The Bible is a divine word for which we need to be ready if we really want to grasp its meaning and communication. This simply means that we need to be holy. It is not a holiness which consists of a string of achievements which we can offer God. It is holiness in the sense of understanding we are in the presence of the Holy, of who we really are, how in need we are to listen, to heed, to receive, to be responsible, to respond.

We are at risk when we take these words in our hands, this text. We do so with responsibility. And with awe. Because, as is always the case, the one who speaks to me, from face to face, may bring me where I never thought I would be.

This is quite a challenge for Bible readers: in taking up the book, taking it into our hands, we realize what responsibility we take on ourselves. We are in the presence of the Other, the human one who speaks about God. We are in a holy sphere. It is a space we enter with deep respect, it is a Presence before which we stand in awe.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

To experience faith and not God.

I found the following intriguing essay about T.S. Eliot. It is a sad reception of this famous poet’s work. It made me think of Nicodemus, but more importantly it made me reflect on what spirituality is really about.

First Things

What T.S. Eliot Almost Believed

________________________________________

J. Bottum

________________________________________

Copyright (c) 1995 First Things 55 (August/September 1995): 25-30.

What passes in the human heart is known to God alone, and the private spiritual life of T. S. Eliot may have been rich and full. But Eliot's publicly presented spirituality-the spirituality in the Four Quartets, Murder in the Cathedral, and The Rock-seems merely weak and strange. Not all spirituality is exuberant or bright, of course. There exists a real spirituality, like John Henry Newman's, that spends itself in the mad, dry attempt to make our inexact words say the exact things of faith exactly, just as there exists a real spirituality, like Gerard Manley Hopkins', that seeks the light of God most strongly in the darkness of His absence. Eliot's spirituality, however, is not precisely dry and not precisely dark; it is instead something like an exotic hothouse plant forced to a small, unlikely bloom-over-cultivated, over-nursed, and over-watched.

For an entire generation of believers Eliot stood as an icon and his faith as a watchword. Born to an age of avant garde art and thought that defined itself most clearly by its rejection of faith in God, Eliot with his gradual-and public-conversion made it respectable again for believers to believe. The respectability was not exactly intellectual, for to the avant garde's amazement there continued to be many intelligent people whose lives were organized around their faith. And the respectability was not exactly moral, for in their gossipy world the British intelligentsia knew too much about one another's private lives for Eliot to claim the authority of a moral hero. The respectability he gave to belief was instead, and more importantly, aesthetic. That a great modernist poet-the author not just of the definitive statement of the Unreal City of modernity in The Waste Land but of so many quotable and right lines about the abyss in "Prufrock," the "Sweeney" poems, and "The Hollow Men"-could come to believe meant that the finest expressions of human life remained available for believers.

Misreading, perhaps, the end of G. E. Moore's Principia Ethica, Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group claimed at least the identity of feeling and morality if not the superiority of feeling to morality. But "feeling" is an equivocal word, and the moral feeling that the Bloomsbury Group meant is not exactly (as Alasdair MacIntyre claims) an emotivism but rather a cultivated aesthetic sense, a self-confirming feel for opposing the finer, more delicate thoughts and things to vulgar, coarse, Victorian self-confidence. And if a man like T. S. Eliot with his obviously delicate feeling could manage to believe, then the modern failure of nerve that so many modern men and women felt might itself contain a new and properly modern-properly delicate, properly aesthetic-path to continued faith in God.

Grace exists where one finds it, and Eliot's example and real gift for turning powerful and right lines probably did help some believers at some moments during this terrible century. But his self-conscious spirituality ends only in paralysis and his delicate spirituality freezes at last faith's difficult search for understanding.

Part of the problem with Eliot's late use of Christian spirituality to fill the void of modern times is that in his early and middle poems he made the void so large. It was with "Gerontion" (1920) in his second volume of poems that Eliot first used deliberate Christian imagery: "In the juvescence of the year / Came Christ the tiger." But the Christ of "Gerontion" serves no more as the Christ of Christian faith than the Agamemnon of "Sweeney Among the Nightingales" serves as the Agamemnon of Greek legend. Since the Battle of the Books, at least, the contrast of ancients and moderns has been a staple of European literature. And when poets of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries wanted to express their increasing discomfort with modern times they found the contrast an obvious trope. Eliot mastered the ironic use of meaningful ancient (and Shakespearian) epithets to indict meaningless modern squalor: though "Her shuttered barge" like Cleopatra's "Burned on the water all the day," still a rich and vulgar American takes her; though "Morning stirs the feet and hands / (Nausicaa and Polypheme)," still Sweeney in a "Gesture of orang-outang / Rises from the sheets in steam"; though "Gloomy Orion and the Dog / Are veiled; and hushed the shrunken seas," still "The person in the Spanish cape / Tries to sit on Sweeney's knees." But Eliot's use of antiquity is not new, and his use of Christianity in "Gerontion" seems an easy parallel to his ironic use of pagan myth-a parallel suggested perhaps by his ironic use of antique churchly words to indict present-day churches in "The Hippopotamus" and "Mr. Eliot's Sunday Morning Service."

And yet, "Gerontion" contains suggestions of something more than the obvious irony of the "Sweeney" poems, suggestions of something Eliot developed two years later in The Waste Land (1922). The poems in Prufrock and Other Observations (1917) make some classical and biblical allusions, but always as aloof and ironic indictments of the emptiness of the characters who speak the poems-as though the poet's own aesthetic feeling and moral sensibility somehow exempt him from that emptiness. In "Gerontion," however, the poet begins to link the allusions with one another and thereby to give them a life of their own. The richness of the past becomes as important as the poverty of the present; indeed, the reality of the past begins to be the fullest indictment of the present-an indictment that the poet begins to realize he himself does not escape.

Midway through "Gerontion," Eliot slips into a meditation on the playwrights John Webster and Cyril Tourneur:

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Think now

History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors

And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions,

Guides us by vanities. Think now

She gives when our attention is distracted

And what she gives, gives with such supple confusions

That the giving famishes the craving. Gives too late

What's not believed in, or is still believed,

In memory only, reconsidered passion. Gives too soon

Into weak hands, what's thought can be dispensed with

Till the refusal propagates a fear.

In the tortured and sinister politics of post-Elizabethan England, in the tortured and sinister syntax of post-Elizabethan playwrights, Eliot seeks an "objective correlative" for tortured and sinister Europe after World War I. History, as the past contained within the present, renders the self-conscious present perpetually ironic, for history perpetually offers possibilities for belief that-the poet supposes-have become impossible for us now to believe.

"Gerontion" is a failure. One problem with the poem is that Eliot cannot find his way back from his historical excursus to the Christ-tiger who makes an unearned reappearance at the poem's end, and another problem is that the complicated politics of England between Elizabeth and the Restoration does not work well as a figure for Versailles after the war. The first problem must wait ten years for a proposed solution in "Ash- Wednesday" (1930). But the second Eliot solves, with Ezra Pound's help, in The Waste Land.

Too much has been said about The Waste Land to make original comment about it possible; it has become, like Hamlet, one of those central works around which criticism feeds upon itself, and everything one says about the poem must finally be about not just the poem but what has already been said about the poem. Eliot himself, with his appended notes and references, made The Waste Land a poem to be read in the context of prior readings of the poem. But Eliot's notes have an even more ironic purpose in the poem, for they prove the extension and richness of the past as past and thus prove the narrow poverty of the present. With the fragmented discourse and simultaneous voices of The Waste Land Eliot finds the objective correlative for the meaninglessness of modern life that had eluded him in "Gerontion." He finds as well, however, with the intrusion of time into the poem, the meaninglessness of modern death-the meaninglessness of his own future death, for though the poet by his creative act may stand outside the chaos he describes (the ascription of meaninglessness is, after all, an ascription of a sort of meaning), he cannot stand outside death. The poem longs for a resolution to the poet's fear of death,

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust

at the same time that it longs for a resolution to the decline of the West,

Above the antique mantel was displayed . . .

The change of Philomel, by the barbarous king

So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

'Jug Jug' to dirty ears.

And other withered stumps of time

Were told upon the walls. . . .

I think we are in rats' alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

T. S. Eliot is a poet of fragments, as Stephen Spender once said, through which run certain great and obsessive themes. And this becomes a vice in the late plays and the Four Quartets, for Eliot realizes his themes insufficiently to pull the fragments into a whole that will reflect the Divine simplicity and the unity of faith. But it remains the greatest virtue of The Waste Land, for Eliot presents the modern mind and modern city as composed of fragments from the past, "a heap of broken images," through which run great and obsessive anxieties. In "What the Thunder Said," the final section of The Waste Land, the anxiety with death and the anxiety with decline at last join: the fragmentation of the poet's obsessive learning and the fragmentation of the Unreal City have a single origin. What the thunder said is "Da"-but if it had said "Datta" (the Buddhist commandment to be generous), the poet and the city would have given with open hands. What the thunder said is "Da"-but if it said "Dayadhvam" (the commandment to be sympathetic) or "Damyata" (the commandment to be restrained), the "heart would have responded / Gaily." What the thunder said is that God has departed from both the poet and the city-and that death and decline alone remain. "He who was living is now dead / We who were living are now dying." The last words of the poem are not the last line's "Shantih Shantih Shantih," but the last note's dry explanation that "'The Peace which passeth understanding' is our equivalent to this word." Eliot reduces even "Shantih" to an ironic fragment, and for the poet and city alike a doomed defense alone remains: "These fragments I have shored against my ruins."

From Matthew Arnold in "Dover Beach" (1867) to Philip Larkin in "Church Going" (1955) poets have found the decay of the culture's religious faith an easy trope with which to express their melancholy sense of lost meaning. But it is a decadent trope and perhaps a wicked trope, for it acquiesces in decay at the same time that it bemoans it and it agrees to inevitability at the same time that it regrets it. Indeed, I suspect that despite the melancholy tone of "Church Going" Larkin actually wishes the utter cessation of faith would come more quickly. Even in The Waste Land Eliot flirts with this trope of lost faith: "Who is the third who walks always beside you?" But he knows philosophy too well to suppose that we could somehow find a meaning for lost meaning, somehow understand why we seem no longer to understand. The reduction of faith in God to an age in history is an attempt to understand faith by surmounting faith, by making the history of faith in God an event transparent to a superior historical understanding. But if the purpose of performing the reduction is to explain why the world no longer seems essentially intelligible, then we lack an explanation for why history should manage to find the age of faith historically intelligible. If the absence of faith in God makes everything meaningless, then even that meaninglessness must be meaningless.

"The Hollow Men" (1925) forms a coda to The Waste Land, for in "The Hollow Men" Eliot purifies in the desert's dry furnace his obsessive anxiety with death and his obsessive anxiety with decline. But he purifies as well his knowledge of the single origin of these anxieties in the absence, not exactly of faith, but of the God in Whom faith would believe-if only we had faith. The philosophically trained Eliot sees that without God, nothing may be beautiful, or true, or good. And here in "The Hollow Men," two years before he entered into Christian communion (on June 29, 1927), Eliot makes the mistake that cripples the spirituality of all his later work.

I must be careful to say exactly what I mean, for certain critics, Marxist or Freudian or postmodernist, dismiss Eliot's late spirituality precisely because it makes an attempt at spirituality-as though Eliot, after looking deep into the abyss in The Waste Land, had closed his eyes in horror and stumbled back into a childish and outdated faith in a childish and outdated God. What I mean instead is that I think Eliot never did truly believe and that his poetry is not about faith's wait for God but about the hollow man's wait for faith. Of course, he probably did believe, and many accounts of personal encounters with the poet describe the deep humility and sincerity of his faith. What we encounter in his late poetry, however, is a profound confusion of faith with a brilliant and learned man's rational understanding that he needs to have faith. It may not have been a confusion in his personal life of prayer, but it is an obvious confusion in his published poetry. And it is still more obvious in his social criticism in The Idea of A Christian Society and Notes Towards the Definition of Culture. Even at his most devout, Eliot sees religion instrumentally-not as Plato's "Noble Lie," of course, instilled in the simple people but disbelieved by the elite, but as a sort of "Noble Truth," instilled in the simple people so that the society may continue but believed in a delicate, ironic, and aesthetic way by the elite. In the anglophilia, misjudged irony, and grotesque delicacy of the worst line Eliot ever wrote-the Magi who have seen the Christ-child reporting, "it was (you may say) satisfactory"-we encounter a spirituality so crippled by its self-consciousness that it testifies only to a mistake in the poet's understanding of faith.

And the mistake originates in the philosophical moves Eliot makes in "The Hollow Men" and extends in "Ash-Wednesday." The failure of modernity rests on the misguided attempt to found philosophical certainty on the self's consciousness of itself, and Eliot rightly sees modernity's failure. But his answer is to force himself to rise to consciousness of his self-consciousness-and then, when he finds that selflessness is not found there, to force himself to rise to consciousness of his self-consciousness of his self-consciousness-and then, when he finds that selflessness is not found there, to force himself to rise . . . -and then. . . . St. Augustine walked this path in the Confessions, and it drove him mad. The notion seems to be that, because we are finite, we cannot (in the real psychology of thought) follow self-consciousness to its apparent infinity; we cannot be infinitely self-conscious. Eventually, at the limit of our thought, we must arrive at a consciousness of which we cannot be self-conscious. Eventually we must arrive at a pure, selfless act of thought that may thereby think the true philosophical foundation of the self.

The path of self-consciousness, however, may be walked only if desire is stronger than reason, only if the will goes on longer than the intellect. The thinker who grows tired and leaps to the conclusion of the apparent infinity of self-consciousness has let reason triumph over weak desire. Augustine falls further and further into self-willed madness as he advances further and further into self-willed self- consciousness, and at last (in a garden as the Confessions tells the story) he converts by the grace of God from madness to that pure and selfless act he sought. But it is a pure and selfless act of will and not of intellect. Augustine becomes an unthinking, irrational, and motiveless desire for the Will of God. And when a child's voice- saying, "Take up and read"-wafts over the garden wall, Augustine drifts as gently as a leaf across the garden and over to the table where he finds the letters of St. Paul.

Augustinian voluntarism provides a philosophical support for St. Augustine's conversion that rationalism could never provide. F. H. Bradley, on whom T. S. Eliot concentrated his philosophical studies at Harvard, found his dialectical idealism-his rational Hegelianism-break down at exactly this point. If the fundamental instrument of the human search for the Divine is the intellect, if the mystical experience is the Aristotelian identity of self-thought thinker with self-thinking thought, then only God could ever arrive at faith. Hegel would be exactly right: the subjective will, because irrational, would be objectively useless and unknowable; history would be the story not of individuals but of God Himself coming in history to freedom, rationality, and self-consciousness. Kierkegaard could not stomach the idea, and F. H. Bradley (at least in a famous passage criticizing Matthew Arnold) apparently could not either. "How can the human-divine ideal ever be my will?" asks Bradley.

The answer is, Your will it can never be as the will of your private self, so that your private self should become wholly good. To that self you must die, and by faith be made one with that ideal. You must resolve to give up your will, as the mere will of this or that man, and you must put your whole self, your entire will, into the will of the divine. That must be your one self, as it is your true self; that you must hold to both with thought and will, and all other you must renounce.

With the demand that by an act of will we give up our will, Bradley reaches toward the Augustinian answer. But Eliot's comment on this passage-"The distinction is not between a 'private self' or a 'higher self,' it is between the individual as himself and no more, a mere numbered atom, and the individual in communion with God"-reveals the extent to which the poet has missed it. The intellect remains for Eliot the organ of faith, just as rationalism (or a sort of rational recognition of the need for supra-rationalism) remains the philosophical support for the search for faith. And the rational self becomes for Eliot more and more attenuated as it walks the path of self- consciousness, more and more ironic, more and more delicate, more and more aesthetic, more and more vague. The poet of precision in "Prufrock" becomes the poet for whom even precision serves abstraction in the Four Quartets. Eliot remained intelligent, of course; if anything, he grew more intelligent as he grew older. His voice deepened as his lines grew denser, and he dropped the boyish trick of using unusual words for their effect as unusual. But he could not find in poetry the faith in God that he saw so clearly he required.

It is not surprising, then, that "Ash-Wednesday" should be the most unified and perfect of the poems after Eliot's conversion. In an essay that appeared shortly before The Waste Land, Eliot claimed that the metaphysical poets John Donne and George Herbert "feel their thought as immediately as the odor of a rose. . . . A thought to Donne was an experience; it modified his sensibility." In "Ash-Wednesday" the thought is still new to Eliot-the thought that knowledge of the need for faith might be itself a kind of faith if only it were felt deeply enough, if only it were experienced deeply enough. And in "Ash-Wednesday" the thought is felt and experienced deeply. "Ash-Wednesday" is a poem not so much about God as prayer for God, and not so much about prayer as about the effort of the poet to put himself in the attitude of prayer. The stuttering fragmentation of lines, developed in "The Hollow Men" to suggest frustrated incompletion, Eliot utterly reverses in "Ash- Wednesday" to suggest consummated completion: just as immediately beyond the spoken line waits the unspoken consummation the hearer expects to hear, so immediately beyond the spoken poem waits the unspoken consummation of faith.

Because I do not hope to turn again

Because I do not hope

Because I do not hope to turn . . .

Lord I am not worthy